What’s the Best Way to Tax Consumers? VAT vs. Sales vs. GRT

A value-added tax is a tax on each step of the supply chain.

For example, if America had a 20% VAT then if you bought iron ore for $60 then how much would you have paid in VAT?

$10.

And then if you turned your iron ore into a bicycle and sold it to a bicycle shop for $120 then how much would you have collected in VAT?

$20.

Once you send your $20 to the government you’d then get back the $10 you paid in VAT so that in the end the final consumer would pay the full 20% VAT ($40) since they don’t get reimbursed.

I simplified the concept as best I could, but even still the VAT is quite complex, especially when you consider that some countries only reimburse part of it on some goods on some steps of the supply chain.

The value-added tax’s complexity is one of the reasons why I prefer a sales tax.

A sales tax just taxes the last step directly!

With a sales tax, only businesses that sell directly to customers are required to collect it, which amounts to an average of 33 hours of paperwork whereas with VAT virtually every business is required to not only collect the tax, but then ask the government for reimbursement, which then amounts to an average of 68 hours of paperwork.

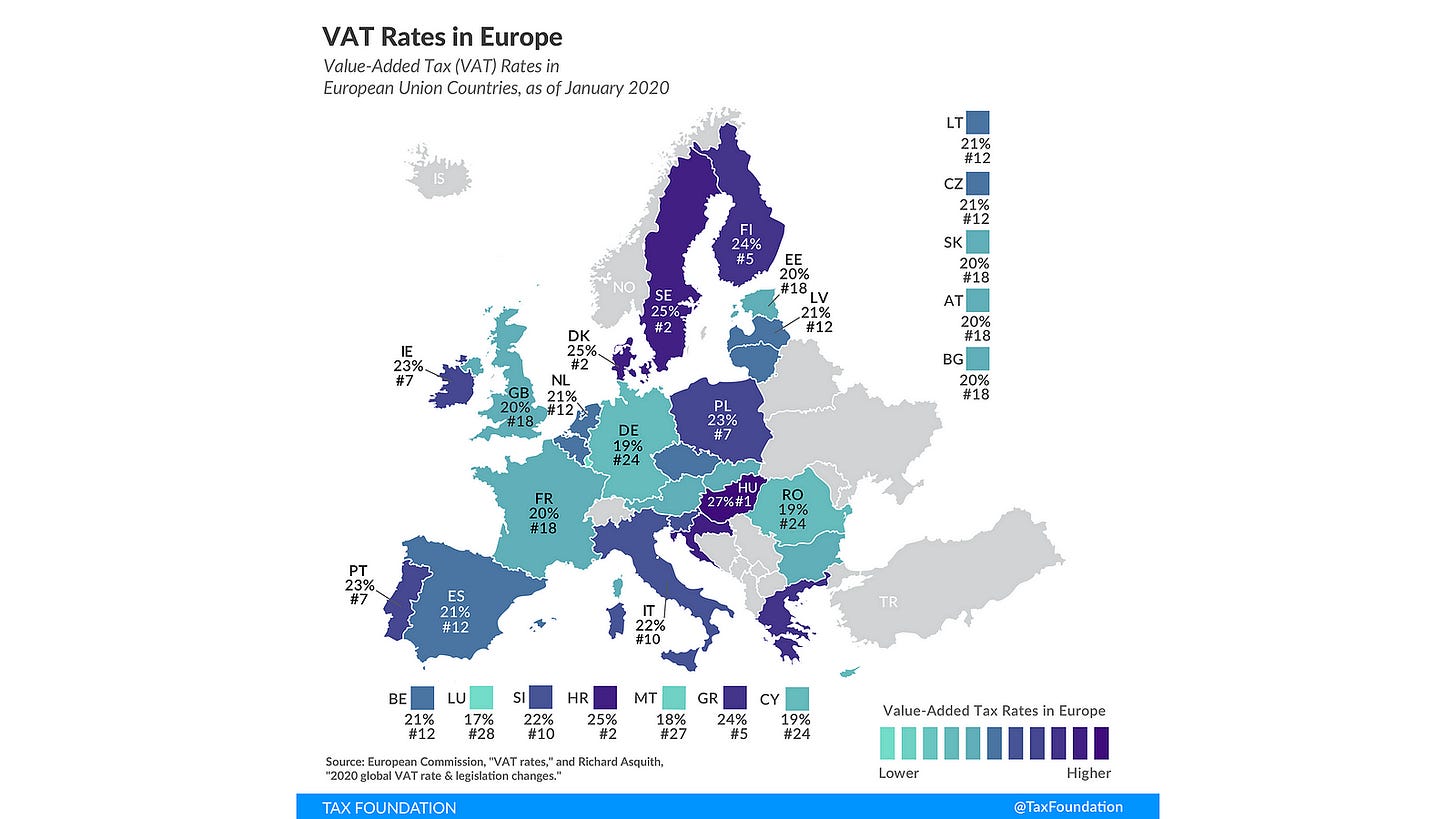

I also prefer a sales tax because it tends to be lower where estimates put the average sales tax at 6.5% and VAT at 21%.

Sales taxes tend to be lower because it’s more transparent since customers see it on their receipts whereas the VAT “blindfolds the people” in some countries as it’s embedded into the price.

Sales taxes are also lower because they’re more avoidable, which means if the goal is to maximize sales tax revenue then its rate can’t be too high since people will buy elsewhere. In other words, avoidability is a feature, not a bug, especially when dealing with regressive taxation.

Another consumer tax that has been gaining popularity is the gross receipts tax.

There are two types of a GRT: sale-side and income-side.

The problem with taxing on the sale-side is it incentivizes vertical integration…

Given the structure of Hawaii’s [GRT] tax, you’re paying roughly a 5% tax at every step of that process… now there’s a very simple solution to that problem [for businesses]. If you integrate the three companies, now there’s only one transaction, so they only pay the 5% tax once. [The tax] encourages the bread company to own its own farm and its own flour mill whereas ordinarily those would be independent companies. — David Friedman

This is why I prefer it on the income-side.

More specifically, I support it on the income-side of corporations (C-I-GRT) aka a gross corporate income tax.

A corporation is basically just a business with a public liability insurance option.

When some of my fellow right-wingers argue for abolishing the corporate income tax what they’re effectively arguing for is passing the cost of reviewing, investigating, approving, and litigating corporations from their owners onto the general taxpayer.

What happened to personal responsibility?!

Now, when I asked some accountants for their thoughts on my gross corporate income tax idea they scoffed…

But what if a business operates at a loss?!

To which I say to these paper pushers…

If business owners don’t want to pay for their government-provided limited liability insurance at say 3% of their gross revenue then they can just unincorporate and buy more liability insurance on the private market.

If more businesses unincorporated then there’d be more political pressure to make the courts more rational again toward actual persons (instead of “legal persons”) so that penalties wouldn’t be as steep therefore reducing the price of privately-provided liability insurance.

Fourth, everything is an expense! Let’s not make the IRS the ultimate arbitrator of what’s a “legitimate” business expense. Trip to Mexico where you spend 15 minutes asking a business owner for advice? Deductible. Trip to Puerto Rico where you walk the beach brainstorming about how to improve your business, which ends up giving you some of the biggest breakthroughs of your career? Not deductible.

Reducing tax arbitrariness is one of the reasons why libertarians like Murray Rothbard supported a head tax, which I oppose, but at least he understood that gross taxation is counterintuitively more anti-tax.

Fifth, a gross corporate income tax makes things stupid simple therefore making it easier for voters to understand the system they’re responsible for holding accountable and it makes it easier for entrepreneurs to compete since they aren’t forced to hire as many paper pushers who have a financial interest in expanding tax complexity.

Finally, my response to tax accountants’ disbelief is, “Yes, we tax losses like the status quo!”

Virtually every tax taxes gross revenue by being completely indifferent to one’s claimed losses.

It doesn’t matter if you have no tenants, you have to pay your property tax. It doesn’t matter if you sell your goods at a loss, you have to pay sales and import taxes (and comply with all sorts of costly regulations like having to pay for your employees’ health insurance). It doesn’t matter if you can’t feed yourself, you have to pay payroll tax. Just to name some of the 97 taxes we pay.

Ultimately, I don’t foresee my gross corporate income tax happening anytime soon, but when I see some accountants clutching their pencils at the thought of losing power I find it even more imperative for us to move in the direction of tearing down their origami walls.

In conclusion, when it comes to taxing consumers let us never do so with VAT, which Republicans considered implementing in 2017 via the Trojan horse that is BAT, and instead tax consumers at an overall lower amount via a sales tax, gross corporate income tax, and as I addressed in a previous essay: a uniform import tax.

Thank you, come again!